Cybersecurity incidents not only begin with a line of malicious code. Many begin with a decision. An employee clicks a link. A manager approves a transfer. A developer shares credentials. In many cases, the attacker does not break the system; they persuade someone to open the doors to it.

Social engineering exploits predictable patterns in human psychology. Understanding those patterns is not optional. For business leaders, compliance managers, and technical teams, it is now a core defence capability.

To resist manipulation, we must first understand how it works.

Robert Cialdini is an American social psychologist, researcher, and writer. His most influential work is Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, published in 1984, where he presents the key mechanisms that drive our will. In this work, he sought to observe and study what tricks "compliance professionals" used in real life to get people to say yes. By combining that practical field experience with his university laboratory experiments, he distilled everything learned into six famous principles: Reciprocity, Commitment and Consistency, Social Proof, Liking, Authority, and Scarcity.

These principles were developed in the context of marketing and behavioural science. Today, they form the psychological foundation of many social engineering attacks.

Reciprocity is the first principle proposed by Cialdini. It works because humans possess an almost biological impulse to return what they receive. If someone gives us value, a favour, or a gift, we feel an immediate psychological "debt" that we seek to settle by saying yes to future requests.

In cyber terms, this may appear as a free resource, urgent assistance, or an unexpected benefit that precedes a request.

The second principle dictates that once we take a small step or adopt a public stance, we will go to great lengths to remain consistent with that initial decision, so as not to appear contradictory to ourselves or others.

Attackers often exploit this by securing minor confirmations before escalating requests.

When uncertainty arises, we look to others. Social proof occurs when we imitate what the majority appears to be doing, assuming that collective behaviour indicates the correct course of action.

Emails referencing “other departments”, “industry standards”, or “most users” are not accidental phrasing.

Liking, as the fourth fundamental principle, tells us we are significantly more likely to be persuaded by people we find attractive, personable, or similar to ourselves. Flattery, shared interests, and familiarity lower our defensive barriers.

In digital environments, this can be engineered through social media profiling and impersonation.

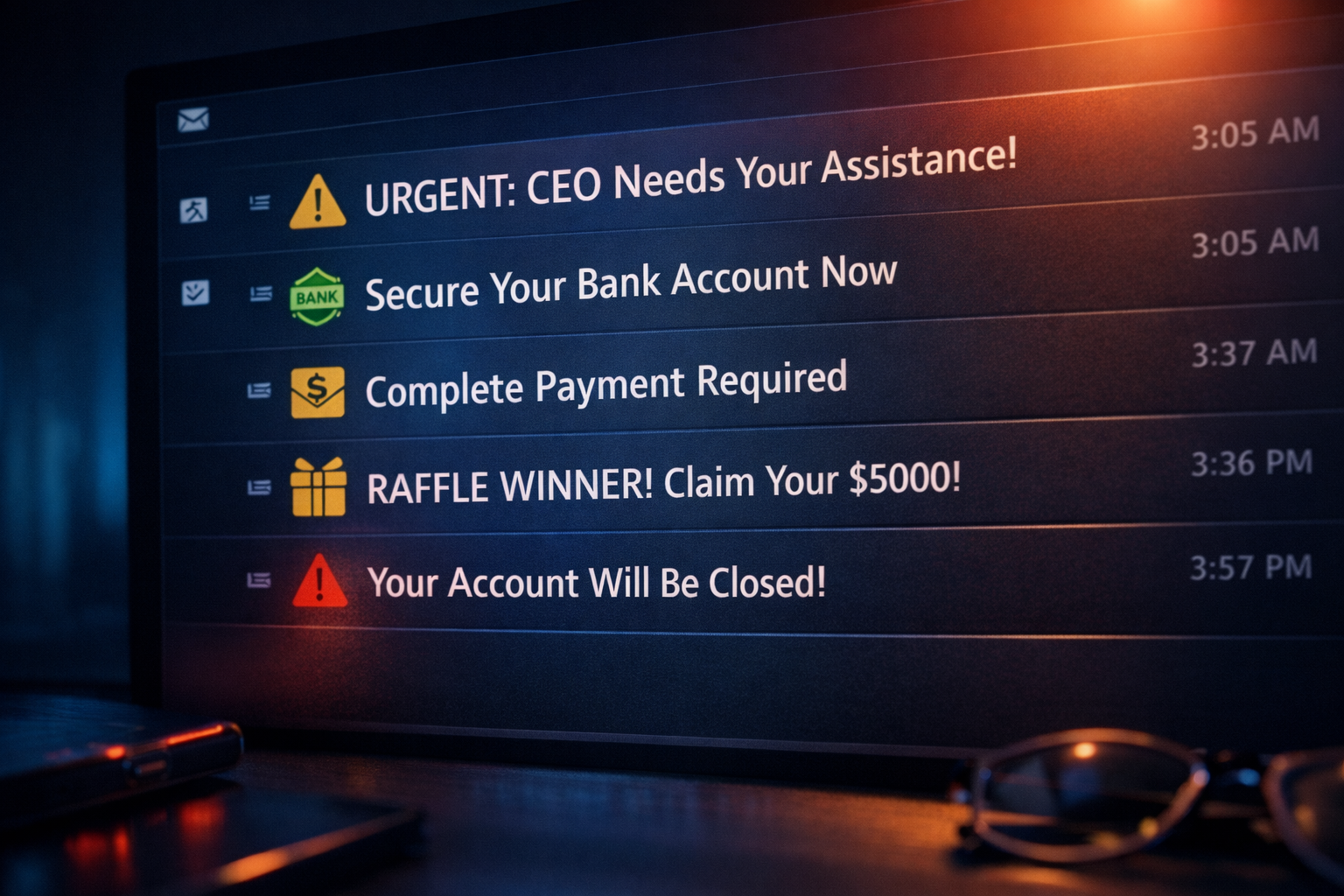

Authority stems from our cultural conditioning. We tend to comply automatically with figures who hold legitimised power or recognised expertise. Symbols such as uniforms, academic titles, corporate branding, or formal language can suppress critical thinking.

Many successful phishing campaigns impersonate executives, regulators, or IT administrators for precisely this reason.

Scarcity explains why we value what appears limited, exclusive, or at risk of disappearing. Fear of missing out often drives action more aggressively than the promise of gain.

Time-limited access, urgent warnings, and expiring credentials are classic examples.

These principles are not inherently malicious. They are neutral mechanisms of influence. The distinction lies in intent.

Cybersecurity, therefore, is not solely a matter of encryption and robust passwords. It is, fundamentally, a psychological battleground. In a digital world where identities can be fabricated with ease, a reflective pause and critical thinking are among the most advanced defense mechanisms we possess.

It is crucial to understand that these principles are not exclusive tools of marketing or sales. Understanding them enables professionals to differentiate between legitimate persuasion and manipulative exploitation. Internalising this knowledge functions as a mental "antivirus", capable of identifying when our own nature is being activated against us.

Recognising artificial urgency, manufactured scarcity, or engineered familiarity is not paranoia. It is operational awareness. Mastering them will not prevent every attack. However, it provides a crucial advantage against social engineering: the ability to recognise that sudden “debt”, artificial “scarcity”, or unexpected “liking” are not coincidental, but psychological hooks designed to override your judgement.

At the end of the day, the most effective defense is not installed with a click. It operates behind your eyes.

You are the ultimate and most important firewall.

Cycubix helps organisations translate behavioural risk into structured, measurable security controls, aligning people, process, and governance. Contact us to discuss how integrated cyber governance and human risk management can strengthen your first and most important line of defence.

Learn More: The Biology of a Breach: How Burnout Became Cybersecurity’s Invisible Threat.